Maria 01, Building 5, entrance B

Lapinlahdenkatu 16, 00180 Helsinki

Making history? lets@maki.vc

Press inquiries: press@maki.vc

Blog | Apr 5, 2019

Despite numerous articles, blogs and tweets about the subject, the inner workings of a venture capital fund, how to get funding for startup, and the related decision-making still seem to be veiled in mystery. As investors, we aim to be as transparent and approachable as possible, which led to the idea of writing this series of posts. During the series, we aim to unveil the mysterious world of venture capital, what kind of companies venture funds are after, and why we sometimes say no to good, even great, companies.

To start with, every VC you’ll ever talk to will ask you about scaling. How big is your total addressable market? How are you going to acquire your customers? Will you be able to grow in revenue without increasing your overheads? Being bombarded with business buzzwords by an inquisitive VC, it’s no wonder the founder often gets frustrated, especially if they are already running a company with proven user traction, steady linear growth or even a profitable business. What else could an investor possibly want in addition to a proven business model and customer traction?

In order to explain why we sometimes say no to companies who are aiming to raise venture capital with an already proven track record, I’ll do my best to explain as simply as possible how the venture capital business model works and how it impacts our decision-making. Hence, welcome to the first part of the series:

========================================================

Venture capital fund is one asset class among many asset classes for the fund’s investors, so called limited partners, or LPs in short. As with any investment, it comes with a certain expectation of return matching the risk reward profile. The limited partners — institutional investors, high net worth individuals and family offices — consider investing in a venture fund risky in comparison to other potential asset classes, such as stock market or real estate. Therefore, the potential upside needs to be significant in order to justify the risk.

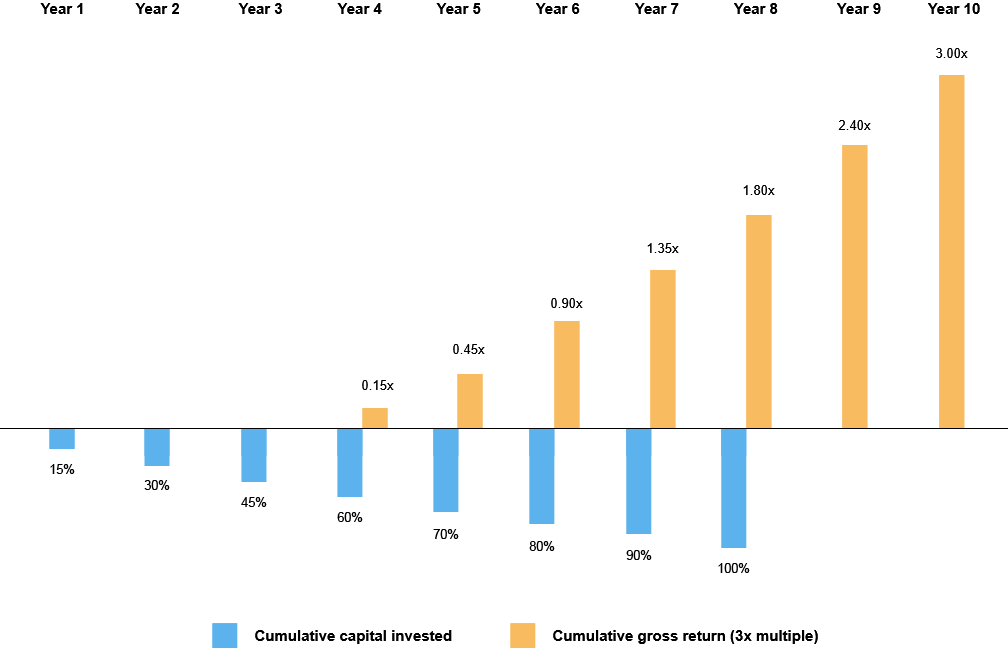

Let’s start by defining what the fund’s LPs are after. I came across a great presentation by seed investor Gil Ben-Artzy, with an illuminating breakdown of average vs. great VC fund performance. According to Ben-Artzy, only 15% of the funds return their funds with a gross multiple of 2–3, and only 5% return a multiple of 3+. For a fund size of 100M€, this means that at the end of the fund lifecycle, let’s say 10 years, all portfolio companies would have been liquidated at a total cumulative value of 300M€.

VCs invest across a set period, let’s say 8 years as in the figure below. Only after 4–5 years, the fund begins to see the first returns as the first companies invested are liquidated. In comparison to other assets classes, such as the stock market or real estate, the VC investments are extremely nonliquid — the investor can at any time sell their stocks or property, but once the capital is invested in a startup or growth company, the investors are not paid any dividends until at the time of an IPO, trade sale or buyout. As an asset class, venture capital is also significantly riskier — according to statistics from early stage venture funds between 2004 and 2013, 65% of an average VC funds’ portfolio companies are no longer operational by the end of the fund lifecycle. These special characteristics make the return expectation for a VC fund significantly higher than for other alternative and more traditional asset classes.

VCs invest across a set investment period and begin to generate returns usually

a few years after the first investment has been made.

Let’s take a 100M€ fund as an example, and let’s assume the fund targets to invest in a total of 30 companies during the 10-year fund lifecycle with an average of 15% stake in each company with an average of 20M€ post-money valuation, and that at the time of liquidation, our stake has diluted to 10%. Let’s also assume that the fund only makes Series A -investments, and that the invested capital is evenly distributed across the 30 companies. Now, it is very likely, if not inevitable, that regardless of the thoroughness of our due diligence and our own contribution during the holding period, some companies will go under or perform only moderately. This means that out of those 30 companies, a handful needs to perform so well, that it can carry the risk of the less well performing ones.

The returns are spread unevenly across the portfolio. A handful of superhero companies will generate the great majority of the total returns.

Now we can get into the topic of scaling. How do the companies that are valued at 50M€ or 500M€ differ from one another, and what have the ones with higher valuations succeeded in in order to generate such a significant value-up?

Companies valued at around 50M€ usually have proven customer traction and an established product-market-fit, and the company is likely to operate in a couple of key markets. All in all, they are usually solid, often even profitable businesses with a steady cash flow. However, often at this stage several companies start to see stagnated growth — usually because the total addressable market proves to be smaller than initially thought, new competitors enter the market and challenge the product-market-fit, the operations aren’t efficient enough, or the business can’t grow in revenue without significantly increasing their costs. These are common problems for example in hardware and service businesses.

The companies with ten times higher valuations generate significant, close to three-digit annual revenue growth-% from a very large addressable market, have figured out a way to expand without increasing their overheads in proportion, the unit economics produce a positive gross margin, and the management team works seamlessly together with a complementing skillset. The move from 50M€ to 500M€ valuation can be best explained with the so called Anna Karenina principle: In order to succeed at scaling, a company must be successful on each and every one of a range of criteria e.g.: product-market-fit, team, proven revenue model, unit economics and operational efficiency. Failure on any one of these leads to stagnation. So, you ask, is it all a matter of luck? The short answer: Yes, a big portion of it is.

In the words of Peter Thiel: ”The biggest secret in venture capital is that the best investment in a successful fund equals or outperforms the entire rest of the fund combined.” The crude generalizations above illustrate how venture capitalists think about scale. Scaling a company from zero to a 50M€ valuation requires a significant effort and can produce nice returns for the owners. However, due to the venture capital business model, we need to be after the ones that have the product, market, operations and enough luck to go beyond that. This is why companies with stable growth, proven business model and a solid team might still not be the right fit for a VC to invest in. This is why service businesses are difficult to sell to VCs. This is also why businesses that target a small niche or a demographic with low disposable income are often passed in VC dealflow.

Due to VC business model mechanics we often have to say no to good teams and great companies, but fortunately, there are other excellent sources of capital — such as business angels, government grants, crowdfunding and corporate venture capital — to support the growth and expansion of new business ideas.

In the next part of the series, we’ll delve into the Product-Market-Fit — in other words, how we evaluate whether the business idea is strong enough to fare against competitive products and solutions, or in many cases, against the inertia of introducing something completely new to the market.

Explore the rest of the 'Are You VC Fundable?' series here:

Are you VC fundable? Part 2: Product-Market-Fit

Are you VC fundable? Part 3: MVP

Are you VC fundable? Part 4: Cap table

Are you VC fundable? Part 5: Team