Maria 01, Building 5, entrance B

Lapinlahdenkatu 16, 00180 Helsinki

Making history? lets@maki.vc

Press inquiries: press@maki.vc

Blog | Aug 26, 2019

A startup’s capitalization table is one of the discussion topics that will, without doubt, emerge sooner or later when talking with VCs. It’s also one of the topics that we encourage founders to spend some time with — whereas almost everything else related to a startup is relatively alterable, the ownership structure gone wrong can be a major pain and, in the worst-case scenario, dilute the key people and thus diminish their future earnings and, have an impact on whether your company is attractive to VCs or not.

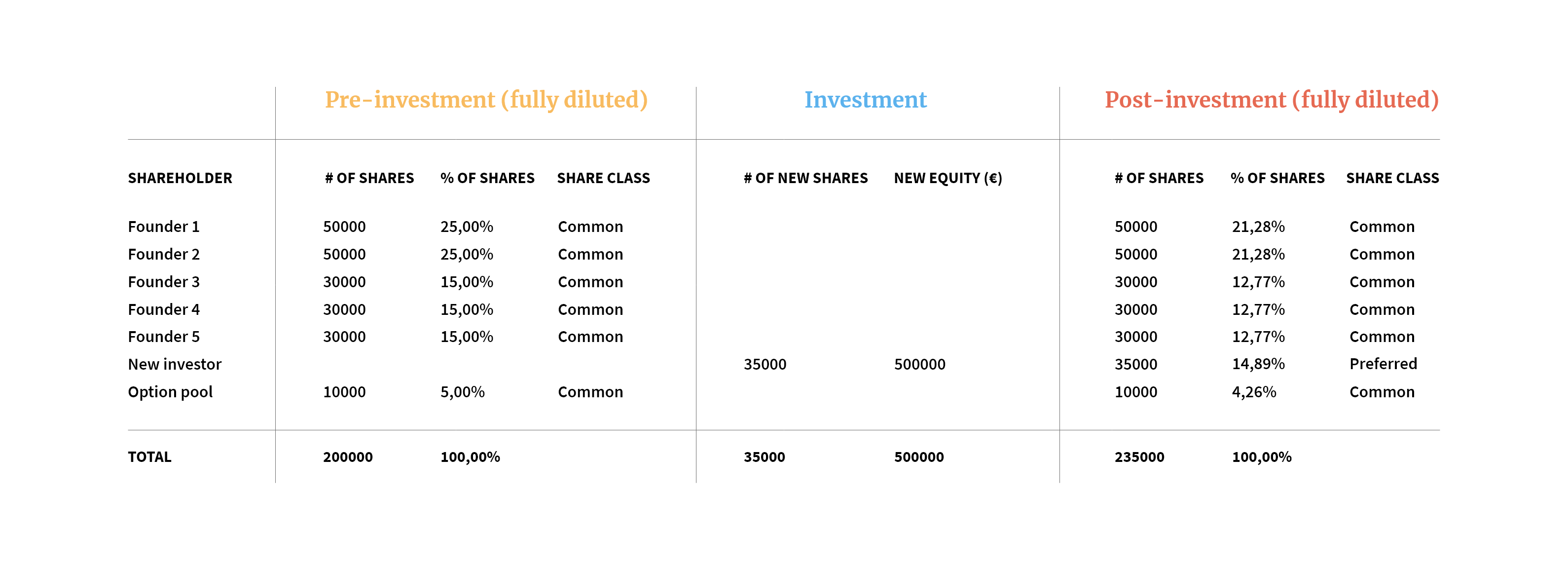

In short, the cap table is a list of all company shareholders, the number of shares, share classes and the percentage of shares they hold. To get fully-diluted equity ownership for each shareholder, you will also need to include the option pool you have allocated for key hires and calculate any possible convertible loans you have given out.

The table above is an example of a company that has five founders. Two of them own 25.00% of the company and the three remaining founders own 15.00%. Usually, the founder-CEO is a majority shareholder, alongside one or two other key players. Other founders may have joined after the majority shareholders have already come up with and worked on the business idea, built the product and perhaps own the potential IP. 5.00% is reserved for future key employees’ options, but more about this later. The total number of shares is chosen relatively arbitrarily, but a good rule of thumb is to choose a number divisible by the number of founders (in this case: five founders, 200,000 shares) or if the number of founders is still up in the air it can be a good idea to choose a number divisible by 60, so that it can be divided equally among one to six founders.

In the example above, a new investor is going to invest €500,000 into the company. The investment required is usually based on the founders’ estimate on how much money they will need in the next 18–24 months for sales, R&D and general administration. Injection of equity usually means the creation of new shares — the share price is based on the company’s valuation.

The primary reason VCs are looking at the cap table is to see whether the operational founders are properly incentivized and committed to the company, meaning that they should own at least 50% of the total equity when in the scaling phase of the company. Founders who own stock even though they are no longer working for the company, advisors with relatively big chunks of ownership or long lists of business angels significantly diluting the founder ownership are usually topics the VCs want to discuss and understand the circumstances behind. VCs prefer tightly-held businesses with “clean” cap tables, as they ensure closer and synergistic relationships with other investors, smooth communication and easier vote collection in comparison to ones with the more complex ownership structure.

Choosing your investors well in the early stages of the company can make all the differences in the future for the firm. It matters who you take money from. In addition to the invested capital, professional investors’ greatest value-add in our opinion is the ability to ask difficult questions, spar ideas and serve as a mentor. They can also support the management team and give connections to potential partners and clients. At best the investor can give a positive touch to future funding rounds when you can show new investors that you have a reputable investor backing you. To conclude, guard your cap table like your life depends on it. As said before, an ownership structure gone wrong can be a major pain. A long list of shareholders without visible value to the company is not something an investor will be happy to see.

In the cap table example, the founders own shares classified as common stock, whereas the investors own preferred stock. Common stock is “regular” stock and preferred stock gives the rights that are agreed upon in the Shareholders’ Agreement. These rights can include things like the majority of the preferred stock shareholders need to approve certain company decisions, such as large investments or divestments, selling part of or the whole company, divesting businesses, liquidation preferences, etc.

So, let’s dig into the liquidation preference. In the easiest terms, it refers to what happens at the time of liquidation, i.e. when the company is sold through a trade sale or becomes a publicly listed company. The 1x non-participating liquidation preference is usually a fair option for all parties involved and is generally thought of as a way for an investor to protect their investment in a risky early-stage company (see Part 1: Scale). A 1x non-participating liquidation preference gives the rights to the 1x returns before other shareholders get anything if the sales price is less than the valuation with which the investor invested. If the sale price is higher, everyone gets their share stated in the cap table. Sometimes a participating liquidation preference is used and a 1x participating liquidation preference means that the investor is entitled to their 1x returns and then to a share of the rest of the liquidation proceeds.

The Shareholders’ Agreement is a contract that has many other important things as well, we’ve tried to pick out some basics that we feel are important but have left a lot of things out that aren’t as relevant when talking about the cap table. It’s good to familiarize oneself with the whole document, seriesseed.fi (Finland), nvca.org/resources/model-legal-documents/ (Nordics) and startuptools.org (USA) have all the relevant documents free to download on their websites!

A very important thing to remember is that the terms in the Shareholders’ Agreement don’t just affect the founders. If you’re an employee at a startup and a part of the employee stock option plan, it’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with the different terms in these agreements and what it might mean in practice for you.

The option pool refers to the Employee Stock Option Plan (ESOP), the legal framework for giving options to employees, which also lays out the standard terms and provisions for stock option grants by the company — a rather complex topic which would deserve its own blog post, so we’ll try to keep it brief. When making an investment in a seed or early-stage company, the VC often requests for the creation of an ESOP. It is a great tool for enticing and incentivizing high-caliber people to join, most often in the crucial company scaling phase. How the stock options are treated and taxed varies greatly between countries, depending on legislation, but they are usually subject to vesting — a predetermined period the employee needs to stay on payroll before the options can be sold, transferred or exercised. If you are employed at a startup or are thinking about it, you should ask about the criteria to get involved.

We often get asked: What do VCs think if there is an angel investor included in the cap table? Do VCs categorically want to get rid of angel investors? Is there some kind of competition between the two?

Let’s get one thing straight — we love pre-seed cases. We always look at every single case that comes our way and can invest as early on as angel investors — we might even syndicate with angels. Sometimes, though, we might advise very early companies that reach out to us to get their first investment from an angel with relevant expertise, build the company a little further, and return to us later.

VCs and angels both have the same objective: to help their portfolio companies off the ground and see them succeed. Compared to VCs, angels as private individuals have less deployable capital and often look for exits earlier than VCs that are after 5–8 year exit times. Angels can be fantastic advisors and mentors in their own area of expertise, whereas VC firms typically have more extensive resources and often leverage their LPs and extended networks in addition to their core teams’ expertise for the good of their investees.

In either case, we advise the founders to be extremely picky regarding the investor they’ll choose, especially in the very early stages of the company, as investors that prove to be not a good fit can be difficult to manage.

Finally, we often see convertible notes listed in the cap table — another topic several founders are eager to hear our opinion on. The use of convertible notes and how they are treated in terms of taxation vary greatly depending on the local legislation. A convertible note is a form of short-term debt that converts into equity, typically in conjunction with a future financing round. Founders may benefit from postponing the setting of company valuation, and the legal paperwork related to financing is much quicker. Convertible notes often come with a valuation cap, hedging the share price of the subsequent valuation round. Another way to hedge the risk of price increase is to agree on a future price discount and/or interest on the loan.

Due to the pricing uncertainty, we feel that convertible notes can place the VCs, founders and other investors at different sides of the table. The worst scenario would be a company initially having multiple convertible notes with different terms and an investor coming in with an equity investment, and all of them having contradictory objectives with regards to the company valuation.

We think that convertible notes are a useful tool for bridge funding in between rounds from existing investors to lengthen the company’s runway when it’s clear that the company is about to achieve milestones that have a positive effect on the value. VCs (or at least us) prefer equity in the initial investment round. The assumption is that a VC can and wants to define a valuation, the contract templates are also ready that keeps the costs low. The terms are also clear to both parties and there are no surprises later.

Explore the rest of the 'Are You VC Fundable?' series here:

Are you VC fundable? Part 1: Scale

Are you VC fundable? Part 2: Product-Market-Fit

Are you VC fundable? Part 3: MVP

Are you VC fundable? Part 5: Team