Maria 01, Building 5, entrance B

Lapinlahdenkatu 16, 00180 Helsinki

Making history? lets@maki.vc

Press inquiries: press@maki.vc

Blog | Jun 11, 2019

And we’re back. In our previous post of the series we talked about Product-Market-Fit and touched the topic of validating and iterating your product in the market. Next, we’ll delve deeper into the iteration process, discuss how to gather useful market feedback and how to apply it in further product development.

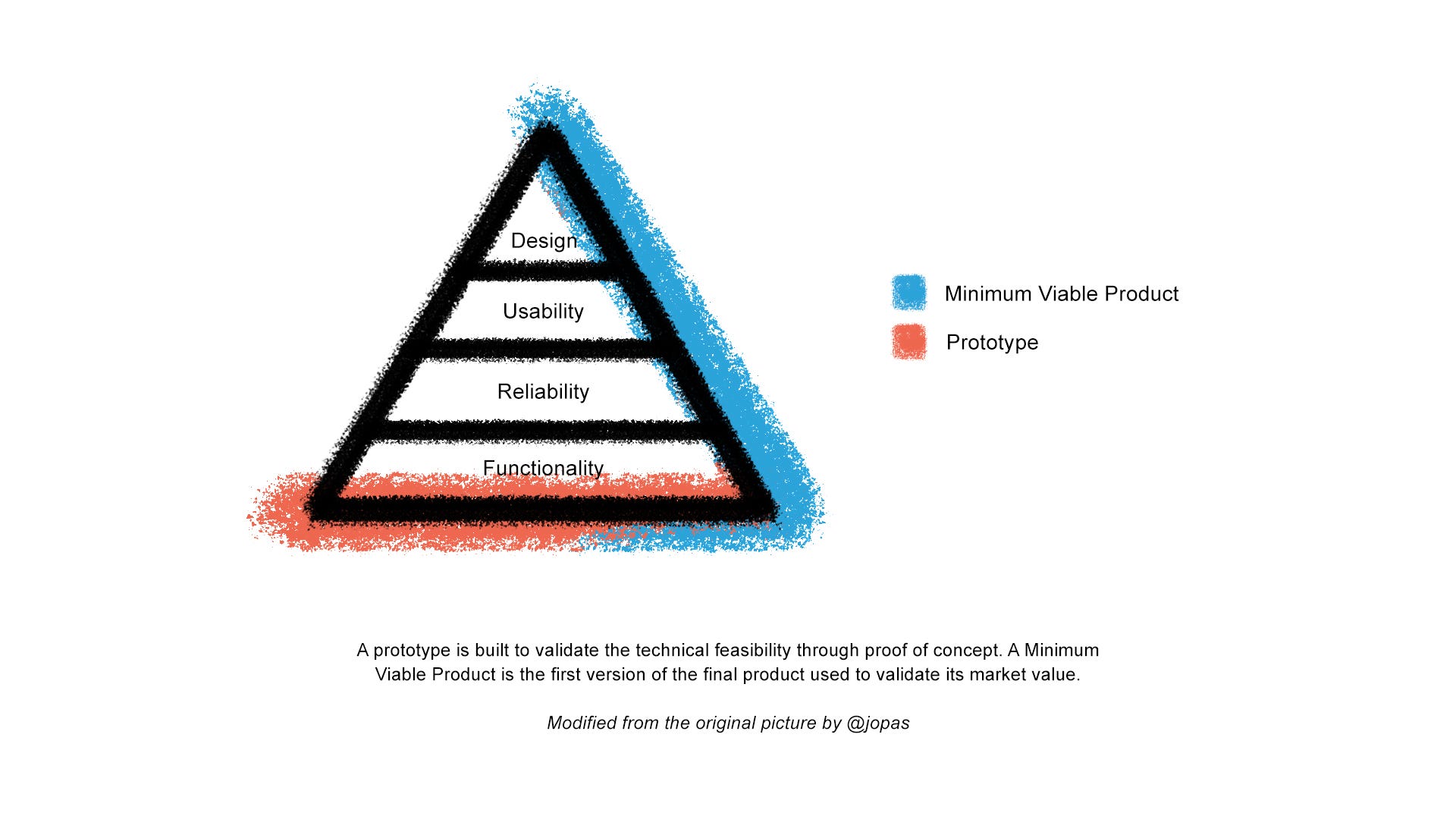

Let’s start with defining a couple of key terms. A prototype is the very first draft of the concept: It’s used to convey the idea and potential to stakeholders — such as investors — either in the form of a mockup, 3D prints or an algorithm that produces results with a limited dataset. Its purpose isn’t to deliver any actual value to the customer, but to deliver a hypothesis, in a form as tangible as possible, on how an identified customer problem could be solved.

Proof of concept is a small project to test whether the prototype or some selected feature or functionality of it is feasible. It can be done in collaboration with a potential end customer, but sometimes the IP risk can be considered too high to share information with outsiders, or the technology can be at such an early stage that the customer involvement would only complicate the project that is supposed to be as quick and simple as possible. A successful proof of concept gives the green light to start the development of the Minimum Viable Product.

A Minimum Viable Product, known as the MVP, is the very first version of the eventual product: it has been proven to work and is already able to deliver limited value to the end customer. The MVP contains a bare minimum of working features and core functionalities and serves as the first touchpoint to the potential customer. Where proof of concept validates the functionality of the technology, an MVP validates whether the product can solve a customer problem and deliver value to the market, often through a pilot. In this post, we’ll focus on the B2B MVP, as B2C is a completely different ballgame.

In theory, pilots are a win-win scenario for both the startup and the corporate customer that de-risk the relationship on both sides before committing to a long-term partnership. In practice, agreeing on the terms can prove to be somewhat tricky.

A pilot should be treated as a stand-alone business opportunity. In addition to having the chance to test drive your MVP in a real environment, there’s often a lot of excitement attached to the potential for future revenue, the benefit of being able to reference a big company, and the potential corporate venture tie-in. However, each of these are separate aspects of the relationship and should be planned and negotiated separately.

The tone of discussion is also heavily dependent on your technology’s role in the customer’s value chain. There’s a big difference whether you’re offering an internal tool promising to make a backend process more efficient, or providing them with something that will become visible to the end customer. In the latter case, it’s likely that your technology has caught the pilot customer’s eye as something that could potentially provide them with a competitive advantage which often opens the discussion on exclusivity, joint venture or even shared IP, depending on how presumptuous the customer decides to be.

An early-stage company’s valuation is largely built on its IP, and therefore sharing it with outsiders should categorically be out of the question. It’s always best to seek out pilot partners that do not require exclusivity, but sometimes it’s the best option available. In these cases, the exclusivity should be strictly limited — both in geography and time and, if possible, in features — and should always come with a revenue or volume target clause.

Another consideration is the pricing. Sometimes the MVP feedback from a client is perceived so valuable that the negotiation power asymmetry leads to an unpaid pilot. This is especially common among large Fortune 500 companies that argue that being able to showcase their logo on your website will significantly shift your position in the market. However, it’s good to keep in mind that the major corporations conduct dozens of pilots based on the same argument, but the conversion from a pilot to recurring revenue is not given, the sales cycles are excruciatingly long, and they often struggle with allocating sufficient internal resources to give you the structured and systematic feedback that, instead of a logo, should be your number one priority.

Discounting your pricing should be your last resort — in addition to the MVP, a pilot is also a way to test your pricing, terms and conditions, onboarding, deployment and service level. Reduced pricing doesn’t mitigate the concerns around an unproven technology but can in fact reduce your viability to deliver a functional, reliable and usable product. To counter-argue the request to work for scraps, communicate that you want to exceed the customer’s expectations and to ensure that you have the resources you need to provide them with an excellent product and service. Try different creative solutions: bundled usage months for a fixed price, X hours of priority support, or two years for the price of one. Reasonable customers want to see you and the pilot succeed, and you cannot afford unreasonable ones — regardless of their brand.

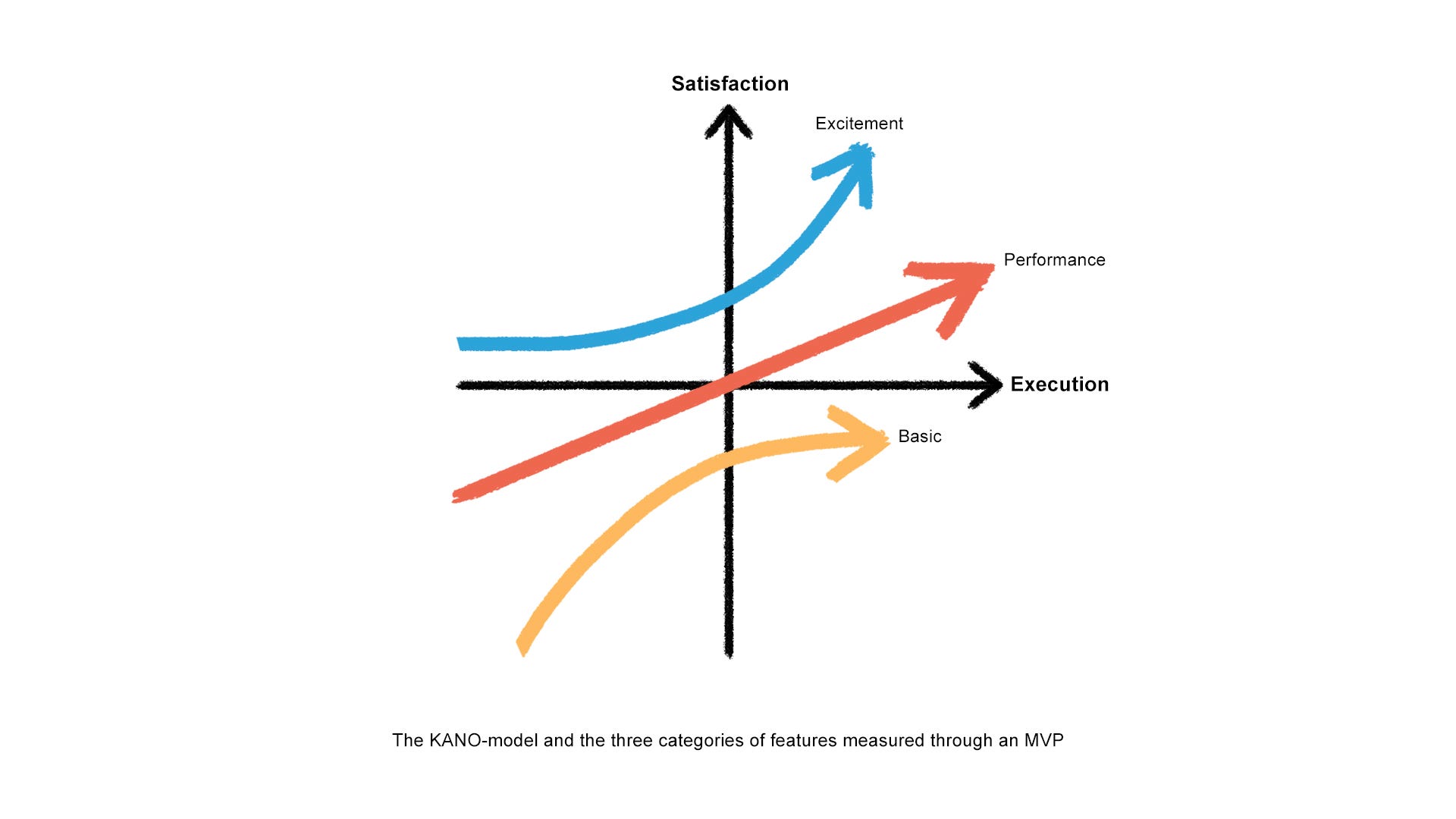

Developing the product through iteration is a concept that every smart startup CEO agrees with, but its practical implementation often remains unclear. A pilot should be treated as a project and structured as one — the collection of feedback entails a lot more than an open question “did you like it?” at the end of the pilot. To test your MVP, you always need a hypothesis, and you need to provide a framework and gently guide the customer to test it. One way to think about the feedback gathering is to use the so-called KANO-model, that separates the features and functionalities into three categories:

Basic: These are the features that the customer requires and takes for granted. The MVP’s task is to prove their viability.

Performance: Additional features and requirements that the customers can articulate and that are on top of their minds when evaluating options. Their value grows linearly — the more you have, the better your product is.

Excitement: Unexpected features and functionalities the customer cannot articulate, but which are the innovations that ultimately separate your product from others.

Another way to guide feedback gathering is to categorize the features into functionality, usability, reliability, performance, supportability and security (FURPSS). The MVP should be developed in sprints with a focus on only 1–2 feature categories at once, and let the other categories gather temporary technical debt. The product roadmap should reflect a set of features that allow entrance to a certain addressable market and to a certain customer category, and how the addition of new features expands the addressable market.

Whom you test your prototypes on will affect the usefulness and relevance of their feedback. On top of the regular users, consider testing on extreme users as well — those who would use the product significantly more than the regular ones, and those who wouldn’t be likely to use it at all. This will help you to get a new perspective on your product, as the heavy users and non-users are likely to be more vocal and opinionated regarding what works and what doesn’t. In addition, always remember to test the product on stakeholders — otherwise moving from a pilot to recurring business might prove to be difficult.

To be VC fundable, the investors often want to see that the product has been in touch with the market and that there is an indication of a group of people that see the value and potential of the final product. Some VCs invest already in the proof-of-concept, but in these cases the technology needs to have either a significant competitive advantage, often through strong IP protection. In order to be VC fundable, always keep the IP in-house, avoid limiting the potential with exclusive agreements, and present a technical roadmap that demonstrates the total addressable market and the features’ relation to its expansion.

Explore the rest of the 'Are You VC Fundable?' series here:

Are you VC fundable? Part 1: Scale

Are you VC fundable? Part 2: Product-Market-Fit

Are you VC fundable? Part 4: Cap table

Are you VC fundable? Part 5: Team